The global monetary system Beyond Bretton Woods 2: The Economist 06 November 2010

The global monetary system

Beyond Bretton Woods 2

Is there a better way to organise the world’s currencies?

Nov 4th 2010 | WASHINGTON, DC

WHEN the leaders of the Group of Twenty (G20) countries meet in Seoul on November 11th and 12th, there will be plenty of backstage finger-pointing about the world’s currency tensions. American officials blame China’s refusal to allow the yuan to rise faster. The Chinese retort that the biggest source of distortion in the global economy is America’s ultra-loose monetary policy—reinforced by the Federal Reserve’s decision on November 3rd to restart “quantitative easing”, or printing money to buy government bonds (see article). Other emerging economies cry that they are innocent victims, as their currencies are forced up by foreign capital flooding into their markets and away from low yields elsewhere.

These quarrels signify a problem that is more than superficial. The underlying truth is that no one is happy with today’s international monetary system—the set of rules, norms and institutions that govern the world’s currencies and the flow of capital across borders.

There are three broad complaints. The first concerns the dominance of the dollar as a reserve currency and America’s management of it. The bulk of foreign-exchange transactions and reserves are in dollars, even though the United States accounts for only 24% of global GDP (see chart 1). A disproportionate share of world trade is conducted in dollars. To many people the supremacy of the greenback in commerce, commodity pricing and official reserves cannot be sensible. Not only does it fail to reflect the realities of the world economy; it leaves others vulnerable to America’s domestic monetary policy.

Related items

-

The Fed's big announcement: Down the slipwayNov 4th 2010

-

The yuan-dollar exchange rate: Nominally cheap or really dear?Nov 4th 2010

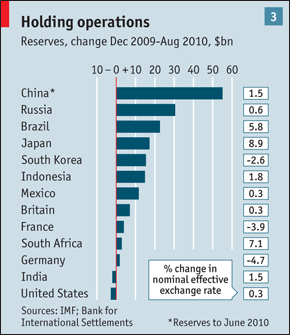

The second criticism is that the system has fostered the creation of vast foreign-exchange reserves, particularly by emerging economies. Global reserves have risen from $1.3 trillion (5% of world GDP) in 1995 to $8.4 trillion (14%) today. Emerging economies hold two-thirds of the total. Most of their hoard has been accumulated in the past ten years (see chart 2).

These huge reserves offend economic logic, since they mean poor countries, which should have abundant investment opportunities of their own, are lending cheaply to richer ones, mainly America. Such lending helped precipitate the financial crisis by pushing down America’s long-term interest rates. Today, with Americans saving rather than spending, they represent additional thrift at a time when the world needs more demand.

The third complaint is about the scale and volatility of capital flows. Financial crises have become more frequent in the past three decades. Many politicians argue that a financial system in which emerging economies can suffer floods of foreign capital (as now) or sudden droughts (as in 1997-98 and 2008) cannot be the best basis for long-term growth.

France, which assumes the chairmanship of the G20 after the Seoul summit, thinks the world can do better. Nicolas Sarkozy, the country’s president, wants to put international monetary reform at the top of the group’s agenda for the next year. He wants a debate “without taboos” on how to improve an outdated system.

Such a debate has in fact been going on sporadically for decades. Ever since the post-war Bretton Woods system of fixed but adjustable exchange rates fell apart in the 1970s, academics have offered Utopian blueprints for a new version. The question is: what improvements are feasible?

The shape of any monetary system is constrained by what is often called the “trilemma” of international economics. If capital can flow across borders, countries must choose between fixing their currencies and controlling their domestic monetary conditions. They cannot do both. Under the classical 19th-century gold standard, capital flows were mostly unfettered and currencies were tied to gold. The system collapsed largely because it allowed governments no domestic monetary flexibility. In the Bretton Woods regime currencies were pegged to the dollar, which in turn was tied to gold. Capital mobility was limited, so that countries had control over their own monetary conditions. The system collapsed in 1971, mainly because America would not subordinate its domestic policies to the gold link.

Today’s system has no tie to gold or any other anchor, and contains a variety of exchange-rate regimes and capital controls. Most rich countries’ currencies float more or less freely—although the creation of the euro was plainly a step in the opposite direction. Capital controls were lifted three decades ago and financial markets are highly integrated.

Broadly, emerging economies are also seeing a freer flow of capital, thanks to globalisation as much as to the removal of restrictions. Net private flows to these economies are likely to reach $340 billion this year, up from $81 billion a decade ago. On paper, their currency regimes are also becoming more flexible. About 40% of them officially float their currencies, up from less than 20% 15 years ago. But most of these floats are heavily managed. Countries are loth to let their currencies move freely. When capital pours in, central banks buy foreign exchange to stem their rise.

They do this in part because governments do not want their exchange rates to soar suddenly, crippling exporters. Many of them are worried about level as well as speed: they want export-led growth—and an undervalued currency to encourage it.

Just as important are the scars left by the financial crises of the late 1990s. Foreign money fled, setting off deep recessions. Governments in many emerging economies concluded that in an era of financial globalisation safety lay in piling up huge reserves. That logic was reinforced in the crisis of 2008, when countries with lots of reserves, such as China or Brazil, fared better than those with less in hand. Even with reserves worth 25% of GDP, South Korea had to turn to the Fed for an emergency liquidity line of dollars.

This experience is forcing a rethink of what makes a “safe” level of reserves. Economists used to argue that developing countries needed foreign exchange mainly for emergency imports and short-term debt payments. A popular rule of thumb in the 1990s was that countries should be able to cover a year’s worth of debt obligations. Today’s total far exceeds that.

Among emerging economies, China plays by far the most influential role in the global monetary system. It is the biggest of them, and its currency is in effect tied to the dollar. The yuan is widely held to be undervalued, though it has risen faster in real than in nominal terms (see article). And because China limits capital flows more extensively and successfully than others, it has been able to keep the yuan cheap without stoking consumer-price inflation.

China alone explains a large fraction of the global build-up of reserves (see chart 3). Its behaviour also affects others. Many other emerging economies, especially in Asia, are reluctant to risk their competitiveness by letting their currencies rise by much. As a result many of the world’s most vibrant economies in effect shadow the dollar, in an arrangement that has been dubbed “Bretton Woods 2”.

The similarities between this quasi-dollar standard and the original Bretton Woods system mean that many of today’s problems have historical parallels. Barry Eichengreen of the University of California, Berkeley, explores these in “Exorbitant Privilege”, a forthcoming book about the past and future of the international monetary system.

Consider, for instance, the tension between emerging economies’ demand for reserves and their fear that the main reserve currency, the dollar, may lose value—a dilemma first noted in 1947 by Robert Triffin, a Belgian economist. When the world relies on a single reserve currency, Triffin argued, that currency’s home country must issue lots of assets (usually government bonds) to lubricate global commerce and meet the demand for reserves. But the more bonds it issues, the less likely it will be to honour its debts. In the end, the world’s insatiable demand for the “risk-free” reserve asset will make that asset anything but risk-free. As an illustration of the modern thirst for dollars, the IMF reckons that at the current rate of accumulation global reserves would rise from 60% of American GDP today to 200% in 2020 and nearly 700% in 2035.

If those reserves were, as today, held largely in Treasury bonds, America would struggle to sustain the burden. Unless it offset its Treasury liabilities to the rest of the world by acquiring foreign assets, it would find itself ever deeper in debt to foreigners. Triffin’s suggested solution was to create an artificial reserve asset, tied to a basket of commodities. John Maynard Keynes had made a similar proposal a few years before, calling his asset “Bancor”. Keynes’s idea was squashed by the Americans, who stood to lose from it. Triffin’s was also ignored for 20 years.

But in 1969, as the strains between America’s budget deficit and the dollar’s gold peg emerged, an artificial reserve asset was created: the Special Drawing Right (SDR), run by the IMF. An SDR’s value is based on a basket of the dollar, euro, pound and yen. The IMF’s members agree on periodic allocations of SDRs, which countries can convert into other currencies if need be. However, use of SDRs has never really taken off. They make up less than 5% of global reserves and there are no private securities in SDRs.

Some would like that to change. Zhou Xiaochuan, the governor of China’s central bank, caused a stir in March 2009 when he argued that the SDR should become a true global reserve asset to replace the dollar. Mr Sarkozy seems to think similarly, calling for a multilateral approach to the monetary system. If commodities were priced in SDRs, the argument goes, their prices would be less volatile. And if countries held their reserves in SDRs, they would escape the Triffin dilemma.

For SDRs to play this role, however, they would have to be much more plentiful. The IMF agreed on a $250 billion allocation among measures to fight the financial crisis, but global reserves are rising by about $700 billion a year. Even if there were lots more SDRs it is not clear why governments would want to hold them. The appeal of the dollar is that it is supported by the most liquid capital markets in the world. Few countries are likely to use SDRs much until there are deep private markets in SDR-denominated assets.

Only if the IMF evolved into a global central bank able to issue them at speed could SDRs truly become a central reserve asset. This is highly unlikely. As Mr Eichengreen writes: “No global government… means no global central bank, which means no global currency. Full stop.”

Nor is it clear that the SDR is really needed as an alternative to the dollar. The euro is a better candidate. This year’s fiscal crises notwithstanding, countries could shift more reserves into euros if America mismanaged its finances or if they feared it would. This could happen fast. Mr Eichengreen points out that the dollar had no international role in 1914 but had overtaken sterling in governments’ reserves by 1925.

Alternatively, China could create a rival to the dollar if it let the yuan be used in transactions abroad. China has taken some baby steps in this direction, for instance by allowing firms to issue yuan-denominated bonds in Hong Kong. However, an international currency would demand far bigger changes. Some observers argue that China’s championing of the SDR is a means to this end: if the yuan, for instance, became part of the SDR basket, foreigners could have exposure to yuan assets.

More likely, China is looking for a way to offload some of the currency risk in its stash of dollars. As the yuan appreciates against the dollar (as it surely will) those reserves will be worth less. If China could swap dollars for SDRs, some exchange-rate risk would be shifted to the other members of the IMF. A similar idea in the 1970s foundered because the IMF’s members could not agree on who would bear the currency risk. America refused then and surely would now.

Rather than try to create a global reserve asset, reformers might achieve more by reducing the demand for reserves. This could be done by improving countries’ access to funds in a crisis. Here the G20 has made a lot of progress under South Korea’s leadership. The IMF’s lending facilities have been overhauled, so that well-governed countries can get unlimited funds for two years.

So far only a few emerging economies, such as Mexico and Poland, have signed up, not least because of the stigma attached to any hint of a loan from the IMF. Perhaps others could be persuaded to join (best of all, in a large group). Reviving and institutionalising the swap arrangements between the Fed and emerging economies set up temporarily during the financial crisis might also reduce the demand for reserves as insurance. Also, regional efforts to pool reserves could be strengthened.

However, even if they have access to emergency money, governments will still want to hoard reserves if they are determined to hold their currencies down. That is why many reformers think the international monetary system needs sanctions, imposed by the IMF or the World Trade Organisation (WTO), against countries that “manipulate” their currencies or run persistent surpluses.

This is another idea with a history. Along with Bancor, Keynes wanted countries with excessive surpluses to be fined, not least because of what happened during the Depression, when currency wars and gold-hoarding made the world’s troubles worse. The idea went nowhere because America, then a surplus economy, called the shots at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944. The same forces are evident today—except that America, as a deficit country, is on the other side of the argument. Like America in the 1940s, China would never agree to reforms that penalised surplus countries.

Such rules would probably be unenforceable anyway. Harsh penalties in international economic agreements are rarely effective: remember Europe’s Stability and Growth Pact? Modest co-operation has better prospects. Just as the Plaza Accord in 1985 was designed to weaken the dollar and narrow America’s current-account deficit, so the G20 could develop a plan for rebalancing the world economy, perhaps with target ranges for current-account balances and real exchange rates. These would be supported by peer pressure rather than explicit sanctions.

A rebalancing plan, which included faster real appreciation of the yuan, would remove many of the tensions in the monetary system. But shifting the resources of China and other surplus countries from exports to consumption will take time.

Meanwhile, capital flows into emerging markets are likely to surge much faster. This is partly due to America’s quantitative easing: cheap money will encourage investors to seek higher yields where they can find them. It is also partly due to the growth gap between vibrant emerging economies and stagnant rich ones. And it reflects the under-representation of emerging-market assets in investors’ portfolios.

For the past decade emerging economies have responded to these surges largely by amassing reserves. They need other options. One, adopted by Brazil, South Korea, Thailand and others, and endorsed by the IMF, is to impose or increase taxes and regulations to slow down inflows. Some academics have suggested drawing up a list of permissible devices, much as the WTO has a list of legitimate trade barriers.

This is a sensible plan, but it has its limits. Capital-inflow controls can temporarily stem a flood of foreign cash. However, experience, notably Chile’s in the 1990s, suggests that controls alter the composition but not the amount of foreign capital; and they do not work indefinitely. As trade links become stronger, finance will surely become more integrated too.

Other tools are available. Tighter fiscal policy in emerging economies, for instance, could lessen the chance of overheating. Stricter domestic financial regulation would reduce the chances of a credit binge. Countries from Singapore to Israel have been adding, or tightening, prudential rules such as maximum loan-to-value ratios on mortgages.

But greater currency flexibility will also be needed. The trilemma of international economics dictates it: if capital is mobile, currency rigidity will eventually lead to asset bubbles and inflation. Unless countries are willing to live with such booms—and the busts that follow—Bretton Woods 2 will have to evolve into a system that mirrors the rich world’s, with integrated capital markets and floating currencies.

Although the direction is clear, the pace is not. The pressure of capital flows will depend on the prospects for rich economies, particularly America’s, as well as the actions of the Fed. Emerging economies’ willingness to allow their currencies to move will depend on what China does—and China, because its capital controls are more extensive and effective than others’, can last with a currency peg for longest.

If America’s economy recovers and its medium-term fiscal outlook improves, the pace at which capital shifts to the emerging world will slow. If China makes its currency more flexible and its capital account more open in good time, the international monetary system will be better able to cope with continued financial globalisation and a wide growth gap between rich and emerging markets. But if the world’s biggest economy stagnates and the second-biggest keeps its currency cheap and its capital account closed, a rigid monetary system will eventually buckle.

Briefings2

.jpg?id=4_638)