How long will the dollar remain the world's premier currency?

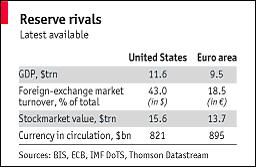

| Losing faith in the greenback Nov 29th 2007 From The Economist print edition  THE long-run value of all paper currencies is zero. That is a fond saying of Bill Bonner, goldbug and publisher of the Daily Reckoning, a contrarian financial newsletter. So why should the dollar be any different? Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Iran's president, seems to think the long run is now: two weeks ago he decried the dollar as a 'worthless piece of paper'. And Jim Rogers, a famously shrewd investor, asks why anyone would buy dollars.  In this period of swelling reserves, the dollar has retained its pre-eminence. It still accounts for nearly 65% of identifiable currency-stockpiles, according to the latest IMF data. This is broadly in line with its historical share (see chart). Factor in the dollars hoarded by China and Middle Eastern oil exporters (not included in the IMF breakdown) and the dollar's share may be higher still.

But although the near-term outlook may be favourable to the euro, its prospects in the medium-term may not be so bright. The euro's appreciation is already causing strains within the currency zone. In the coming decades the euro zone's workforce is set to age faster than America's, which will hamper its economy and add to its fiscal pressures. There is also the question of how much trust investors will put in a currency with no central fiscal authority to stand behind it. Since the title of reserve currency can be split, the dollar's share in global currency reserves is probably too bigwhatever happens to foreign-exchange rates. Many of the countries that have built large stocks of dollar assets by pegging their currencies to the greenback are now battling with inflation. Sticking with the peg would mean importing the policies of recession-threatened America and feeding inflation still more. Yet abandoning the peg only adds to the pressure on the dollar. A compromise is to be weaned off the dollar, with a peg made up of a basket of rich-world currencies, including the greenback. This would give dollar-peggers more freedom over their monetary policythey would no longer have to mimic the Fed slavishlywhile allowing them gradually to slow their purchases of dollars. Is a dollar rout avoidable? An optimist would say that central banks, having spurned the chance to diversify out of dollars when a euro could be bought for 86 cents, are unlikely to want to switch now when the price is close to $1.50. Against conventional benchmarks like purchasing-power parity, the euro looks dear against the dollar. So it could be a bad time to swap from one horse to another. To the extent that dollar-holders act like an informal cartel, then the biggest dollar-holders will set an example. Japan seems unlikely to start selling its huge dollar reservesif anything it might intervene to prevent the dollar falling further against the yen. A crash might be averted if China holds fast too, because it recognises how self-defeating dumping dollars would be to such a large owner of American assets. Yet a pessimist would counter that a revaluation of emerging-market currencies against the dollar could easily turn disorderly. Although economic logic may argue against selling dollars at a cyclical low point, central banks have sometimes been hopeless portfolio managers: witness their shift out of gold just as its price hit a low. Yes, the dollar looks cheap, but currencies often overshoot. So it would be foolish to say where its decline should stop.

|

.jpg?id=4_638)